A Journey To Boston

- I’d be building a 44mm flieger style watch

- I’d be assembling a hand-wound ETA 6497 movement

- Lunch would be provided

Saturday

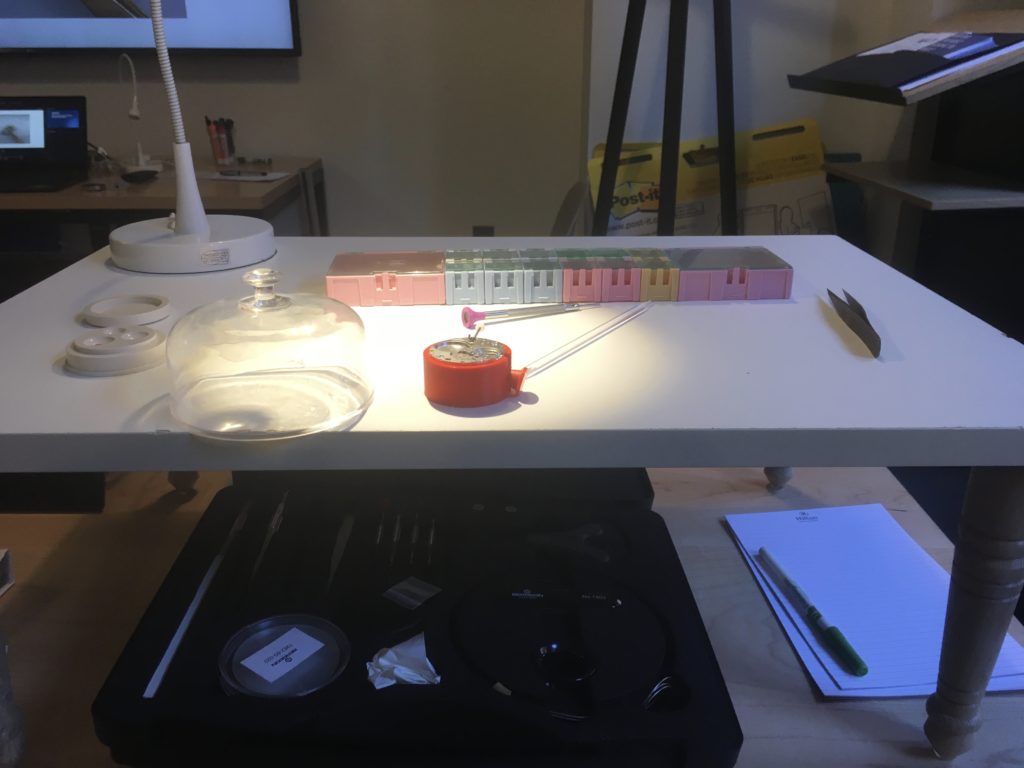

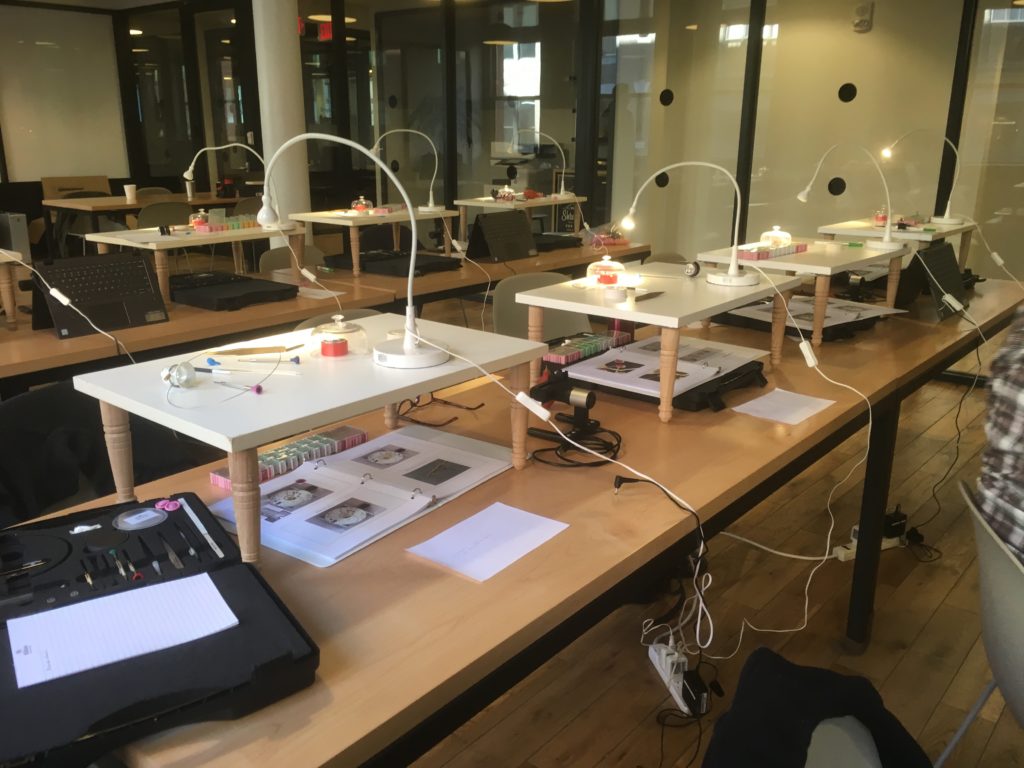

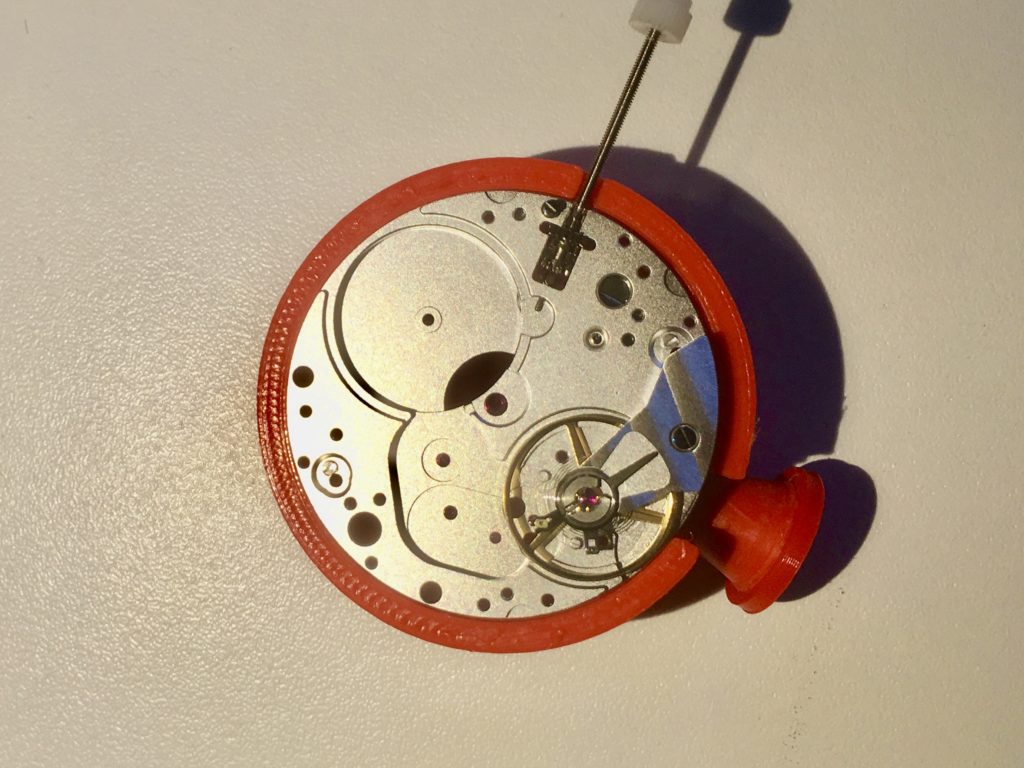

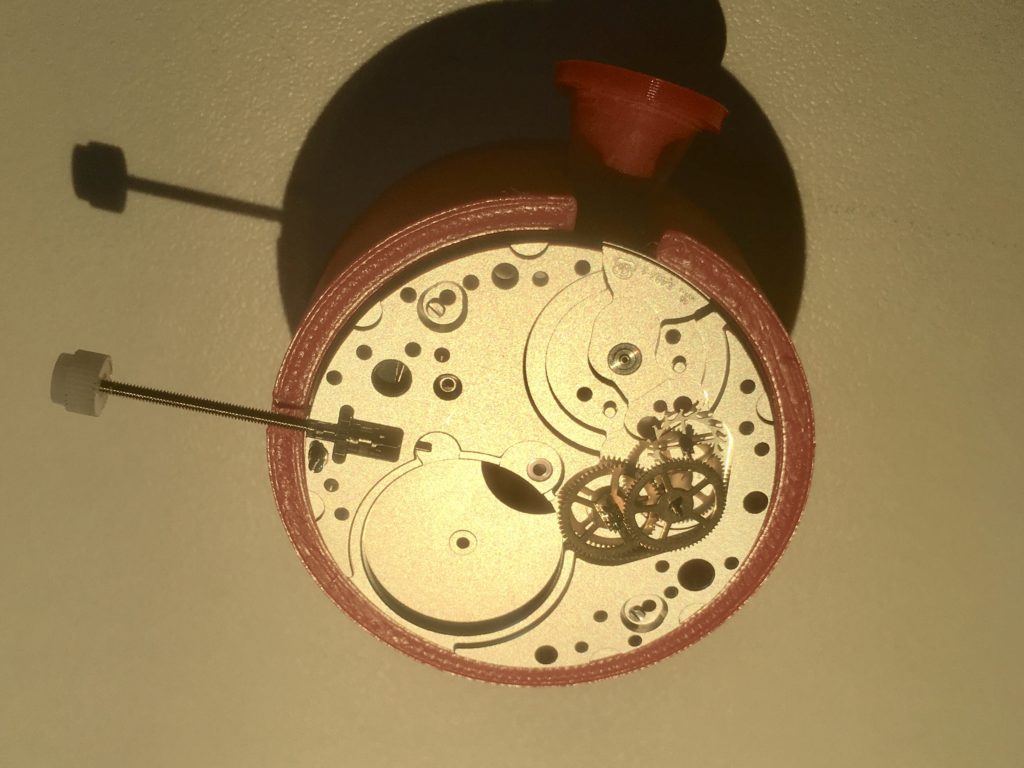

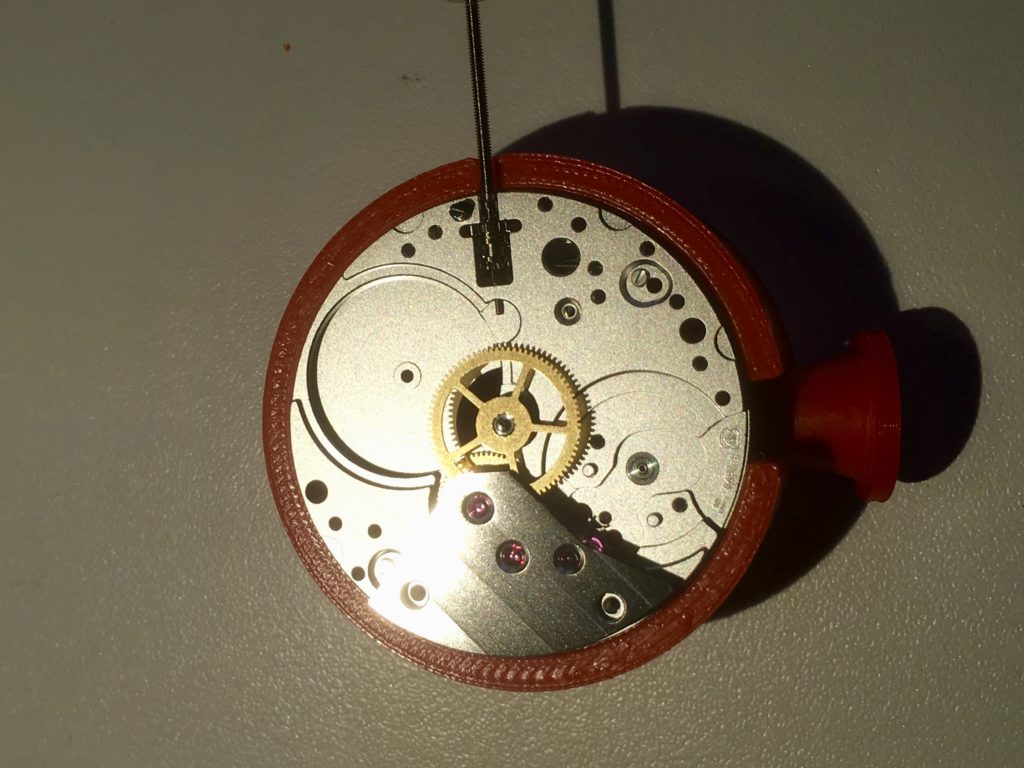

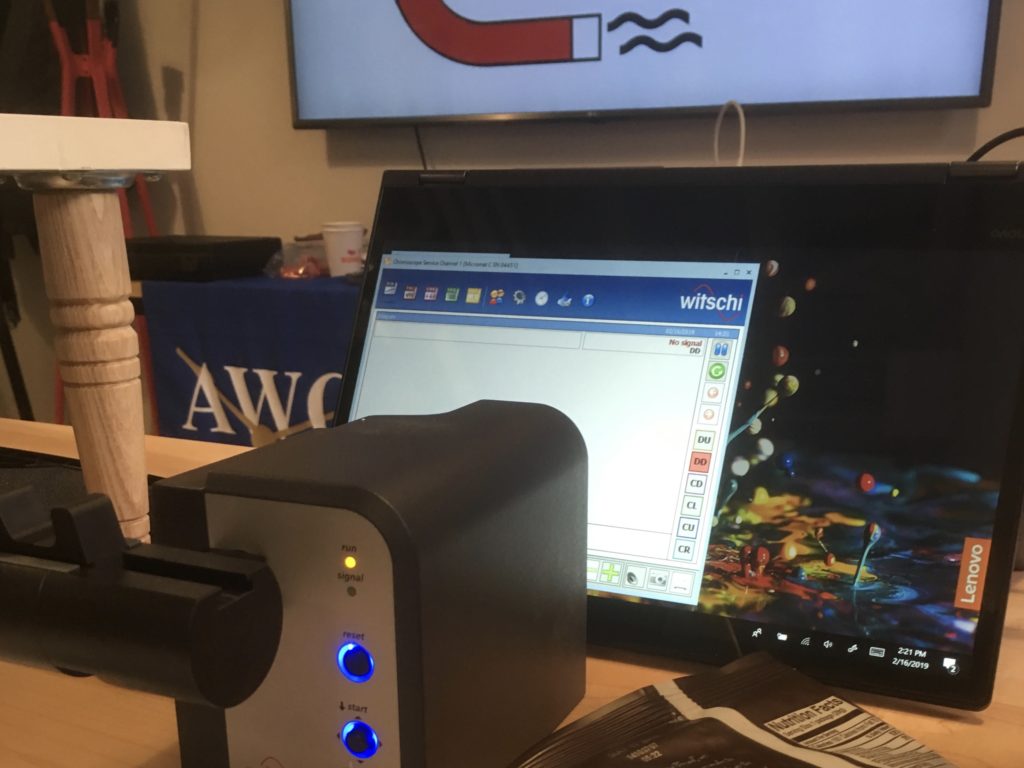

The first part of building our ETA 6497 was to hold its bones in a bright orange 3d-printed movement holder. I’m not certain as to why there wasn’t one contained within the set, but it was cool to see a tool built specifically for the class. We put on our loupes and carefully began to open our pillboxes. The tools most utilized were screwdrivers, brass tweezers, and an acrylic poker. The set was a nice one, and we were told we could take one home for the low low price of $299 (which really isn’t a bad deal)!

Reflections

The most surprising takeaway from my experience was that the movement we worked with was large, even by modern standards, meaning I can’t even imagine the amount of precision involved in manipulating smaller movements. I have a respect for watchmakers that I’d only had in theory before. Actually doing the work made me realize how intricate everything is and how much control one needs to have over one’s hands and mind.

The most difficult time I had was lubricating parts. In some situations, we’d have to hold a part with tweezers in one hand while applying lubrication with the other. The challenge was twofold: scooping up the exact amount of lubrication on a microscopic shovel, and then applying said lubrication to the exact area of the part all while looking through a loupe. The first gear I lubricated took me a couple of tries, as I’d applied too much resulting in it dripping down into a pinion. The second time I didn’t apply enough (I was gun shy)… and the third time, well, I got lucky.

All in all it was an incredible experience and quite a bit of work that required 100% focus. The three watchmakers that ran the classroom were amazing and had unlimited amounts of patience. I am confident that I would NOT have left with a working watch without them.